Ever feel you might be writing the wrong story?

Let’s say you have a great premise and the characters are fully realized in your own mind. You rush to get something down on the page, either in the form of a detailed outline or a rough first draft. Everything goes pretty well for the first bit, but at some point you start to second-guess yourself.

The plot just doesn’t seem to be meshing as well with your characters as you thought it would. You’re having trouble translating your initial vision onto the page. You begin doubt you have the skills to make the story everything you wanted it to be.

Does all of this mean you chose to write the wrong story? Should you cut your losses and move on to the next idea?

While this may be the case some of the time (for example, you’re attempting to write a story that necessitates knowledge you can’t acquire through research), in many cases…

…it’s less about writing the right story, and more about writing the story right.

There’s No Such Thing as a Small Story

You know how, in the acting world, they say there are no such things as small parts, only small actors? That means even the smallest of roles can be memorable, and played with depth and enthusiasm, given a talented actor.

My theory is that the same truth holds for writers and their stories. There is no such thing as a small story, only small writers (that is, writers who think small in terms of the story—those who cannot do it full justice).

Think about it. Wonderfully powerful stories have been written about relatively everyday or mundane concepts. For example, John Cheever’s The Swimmer is about a man who tries to get home from a friend’s house by swimming through all the pools in the county. Hardly anything happens in the story, but it features a lot of symbolism and has a surprise ending which makes it a classic.

But, told in the wrong manner, that classic could have been a complete flop.

Is Your Story Too Big for You?

I started writing a short story a few months ago, one which came to me like a lightning bolt. I knew where I wanted to go with it, and did a basic outline. But once I had written a skeleton draft, something just felt wrong. The plot was unfolding in two contrasting locations, and for that reason it felt as if I were trying to tell two stories instead of one. The more I second-guessed myself, the more my characters began to slip out of focus. I felt I was in over my head. Perhaps this wasn’t the right story for me, or for these characters.

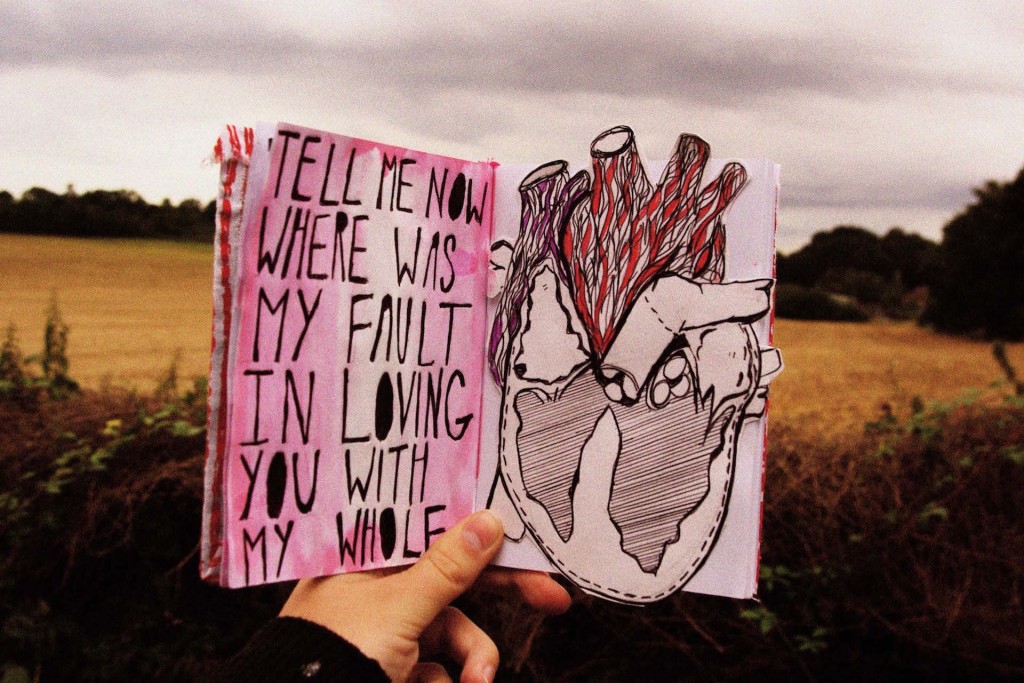

But, for some reason, I just couldn’t abandon it. It meant something to me on a personal level. It was a big story, not in terms of plot, but in terms of depth. It would require plenty of blood, sweat and tears to make it the best it could be.

That’s when I realized that it wasn’t a matter of me having the wrong story; it was a matter of me not telling the story in the best way possible. The dual settings could work so long as I found a way to better connect them to each another and to the plot. The characters could become what I had initially envisioned with some more fleshing out. I could find the best narrative point of view by testing a few parts in first and third person. And, some parts which I had already written—but weren’t really working—needed to be discarded.

The story didn’t need to be abandoned. It just needed to be told in a different manner. It was my job to discover what that meant.

Writing the Story Right

In A Brief History of the Short Story, Part 37, The Guardian claims Alice Munro once remarked that she eschews definite conclusions in her stories because:

“I want the story to exist somewhere so that in a way it’s still happening, or happening over and over again. I don’t want it to be shut up in the book and put away – oh well, that’s what happened.”

To me, that’s the definition of writing the story right. Where the story and characters actually live on in the readers mind, in some sort of alternate universe, long after the pages are closed.

How can we make sure we’re writing our stories in the best way possible?

- Persevere. Some stories will simply fall out of your fingers, and other times you won’t be so lucky. Think of it this way: if a story comes too easy, there’s a good chance you could have written it better. It might be good, but is it the best it can be? When you’re tempted to say ‘it’s finished,’ leave it alone for another week and come back to it again.

- Understand what your characters want. Character motivations are powerful. What’s the main thing your character wants? What are her goals and dreams? As readers, we need to not only be told what your characters need—we must be made to believe it and feel it ourselves, to some degree. We have to want to see those characters achieve their goals.

- Experiment. When you just don’t know what the problem is, you may need a little experimentation to help your story along. You can always copy it into another document in order to try on different points of view or writing styles, or add/axe characters or subplots. Sometimes just rearranging existing parts of your story can make a big difference.

- Break the rules, if necessary. There really aren’t any rules with writing. There are tried-tested-true guidelines, but no absolutely never-ever-break-’em rules. Sometimes, telling your story right means you go against the grain. Just make sure you understand why you’re going against the grain.

- Write with your heart, but edit with your head. Writing just with your heart can result in a sloppy mess. Writing just with your head means you overthink things and don’t give yourself over to your creativity. It’s been said that first drafts are for telling the story to yourself. Write with your heart first so you have the freedom to be creative, but edit with your head to polish your story.

We may not finish every story we toy with, but I think we seldom begin writing stories so wrong for us that they cannot be completed. Any story can be memorable and well-written, given the right artist to craft it.

Can you share an example of a time when you successfully overhauled a story you would normally have abandoned? Do you have any further advice for writers struggling to tell their stories in the best way possible?